Analysis of Ambiguous Memory

Summary

Maxwell Riggsbee, Sr.’s memory begins in a period of success and stability immediately following World War II, noting that “World War II was ending in the spring of 1945, and my father’s businesses were successful”. Life at 728 Atlantic Avenue, located in the cross town district of Rocky Mount, was a “happy time”. As his father’s businesses expanded, so did the “quality of our lives,” resulting in an updated home, a nice car, and home mail delivery. One significant community achievement was the city paving the 700 block of Atlantic Avenue and adding concrete sidewalks—an improvement influenced by his father’s status and Kay Kyser. This allowed Maxwell to happily skate in front of his house on his Union Hardware ball bearing skates. These blocks were even closed on summer Saturday afternoons for “Colored children” from across Rocky Mount to come and skate.

Education, Identity, and Segregation

During his years at O. R. Pope Elementary School, the first week of February was designated Negro History Week, a very special time when pictures of “famous and well-known colored people” (including abolitionists, inventors, and educators) were hung by theme throughout the hall. Starting in the fourth grade, students were required to select one of these figures and write a short story. Maxwell recalls that his mother helped him research the “colored sailor” Doris Miller, whose picture did not hang on the wall, forcing him to rely on newspaper articles to write his story. In the fifth and sixth grades, Maxwell continued to focus his writing on “colored military heroes whose pictures did not hang on the walls”.

The 1947–1948 school year marked a difficult transition to the “colored Lincoln Elementary Junior High School,” located a mile and a half away in the Happy Hill neighborhood. Maxwell had to walk the long way to school, crossing the Atlantic coastline railroad tracks and US 301, a main highway, specifically to “avoid walking through an all white neighborhood”.

The Trauma of Abandonment

This period of “relative peace” was violently replaced by “devastation and hardship”. In late July 1948, Maxwell woke to the sound of his mother sobbing, learning his father had left. His father was moving to California to be with Mr. James Kyser and marry Marian, who had worked as his waitress/cashier at Max Cafe.

The abandonment was especially traumatic because of the nature of the father’s affection. While Maxwell’s sister, Clementine, “loved my father, and he loved her,” and was constantly called “doll baby”, Maxwell notes that his father was “affectionate with her unlike with me”. Maxwell, his mother, and Clementine “never forgave him for walking away”.

Lost and Found

The resulting burden of emotional pain stems from what Maxwell describes as an “ambiguous” memory of his father. He could “never remember my father hugging me or saying I love you”. He even recalls overhearing his mother telling his father that “he needed to pay more attention to me”.

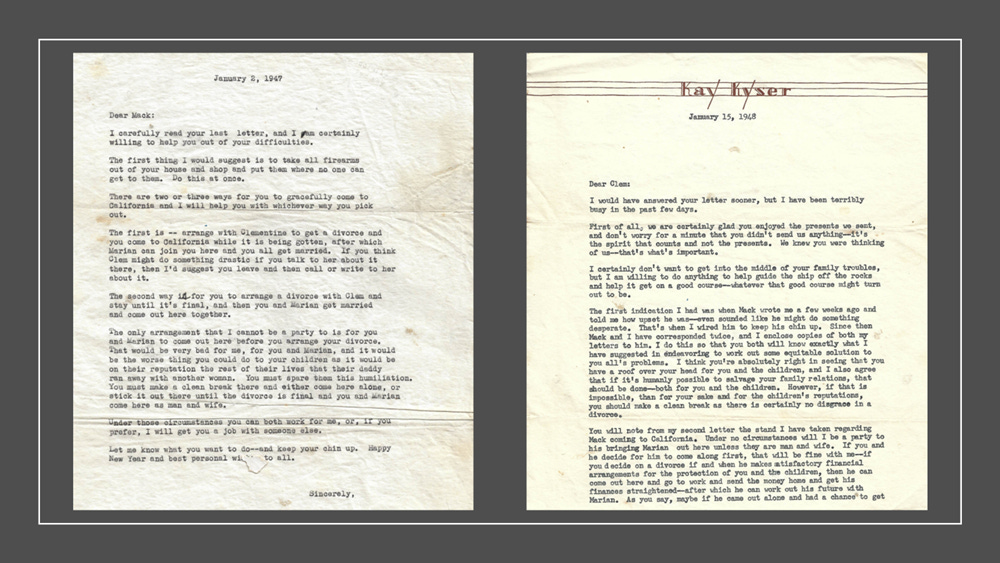

Years after his mother’s death in 1989, Maxwell discovered letters that revealed the full extent of the abandonment. He found correspondence from his father to Kay Kyser expressing a subservient desire to join him in California with Marian. Maxwell was—and remains— “incensed that [his] father was so subservient”.

He also found letters from Kay Kyser, who advised his father on how to “gracefully” handle the marital problems and exchanged letters with Maxwell’s mother, advising her to “stay strong for her children”. Maxwell found Kyser’s letters to his parents to be “condescending, intrusive and patronizing,” resulting in ongoing anger toward Kyser for his role in the separation and divorce.

Reflecting on this history, Maxwell Riggsbee, Sr. concludes that his father “never got to know me” because he never allowed people to see “the weight of the pain” he lived with as a child and young adult. He states definitively, “I am the me nobody knew, especially my father”.